by Vladimir Zlacky | Apr 8, 2020 | | News

In my blog from December 2018 – Is the advanced East as rich as Southern Europe? – I tried to flash out why it is worth looking at nominal variables alongside the real ones when gauging the state of convergence of the Eastern European countries to the developed West. This blog argues that nominal figures are overlooked in many cases also in some other contexts.

Let’s take a simple question: Which is the biggest economy in the world? Is it still the US or has China overtaken? The answer depends on which figures one looks at. According to the official IMF statistics of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 in nominal figures, the US still is the biggest economy, its GDP was 21 439 bn USD while that of China was only 14 140 bn USD (even the economy of the EU was bigger than the Chinese one, its GDP in nominal prices was 18 705 bn USD in 2019). However, given that prices of goods and services in China are typically much lower than those prevailing in the US when adjustment is made for differences in prices ( re-calculation based on so-called Purchasing Power Parity metric), the Chinese economy is the world’s most productive with the GDP based on PPP 27 309 bn USD while that of the US is 21 439 bn USD ( the US is a base country for PPP calculations). In a nutshell, the US has the world’s biggest economy in nominal USD terms while China prides the world’s most productive economy based on the PPP recalculation.

Which set of numbers is more relevant for policy analysis? Figures adjusted by PPP suggest how productive the real economy is in terms of produced goods and services – hence the given figures for the Chinese economy suggest that China has the most productive economy in the world in terms of real output. However, when we would intend to calculate the size of the economy in terms of “the sheer economic mass” – perhaps to suggest how economicly powerful the individual countries are – then nominal figures might be more useful. In other words, the actual world in which we live is nominal: wages, prices of goods, sales or capex of firms, macro- capital flows or debt all are nominal variables. Economic figures adjusted for price differences are an artificial construct of economists. While they might be useful for economic modeling and analysis, an individual does not observe them in the real world.

Since we are using the figures of IMF, an additional small comment might be useful here. According to the World Economic Outlook, the world’s GDP growth projection for 2020 is 3.3 %. This is just illustration – this figure is now probably obsolete and given the current unfolding crisis it will be much lower. However, the real question is as follows: Is this the projected growth of the world economy by the IMF in PPP, constant prices or is it a growth of the world’s nominal GDP (in USD)? While the Fund in its headline communique does not say so explicitly, from other IMF outputs it can be inferred that it is a figure based on GDP growth in constant prices of individual countries. Many companies in the world and its planners who prepare company-level projections might compare the growth of their relevant world market with this headline figure. However, the relevant figure should be the growth of the world’s nominal GDP, not the real one. This is because corporate-sector planners work with sales figures in nominal terms recorded in the actual world.

How high is then the growth of the world’s nominal GDP in normal times? Probably significantly higher than the current projection of 3.3%, given a high nominal GDP growth in China and other emerging market economies and existence of inflation nearly everywhere(nominal exchange rate fluctuations vis-a-vis the dollar obfuscate otherwise straightforward calculation). A little speculatively, the world’s nominal GDP growth in USD could be 1-2 % higher than the figure based on the constant prices, in normal times.

One last comment of somebody who has prepared company valuations before. When valuing a company, say with global sales, using a discounted cash-flow framework one splits projection into two stages – an explicit projection phase and approximation of terminal value using the so-called Gordon growth formula. However, where do we cap the growth of a company’s cash-flow in the terminal value formula? Clearly, the rate of growth of the company’s cash flow in perpetuity must be below the cost of capital, otherwise, the model is invalid. Additionally, in the Gordon growth formula, the permanent growth of the cash-flow of a firm should be further below the projected long-term growth of the world economy, lest the company would overtake the whole world in an infinite horizon. However, which growth rate of the world economy shall we use as a ballpark of the upper limit? In the author’s opinion – since everything in the cash-flow model is in the nominal figures – the relevant ceiling is the rate of the growth of the world economy in nominal terms (let’s say, in USD), rather the growth rate based on constant prices.

Does this imply that some market participants might systematically undervalue assets?

Vladimir Zlacky

8 April 2020

LookingEast.eu

by Vladimir Zlacky | Oct 26, 2019 | | News

The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) applied to many sectors of national economies and thus driving Industrial Revolution 4.0. will likely bring a large increase in output and labor productivity in economies of Central and Eastern Europe. This is because the nature of work will change due to robotization and the application of AI to new technologies will likely bring revolutionary breakthroughs. Also, our lives, professional and otherwise, will be transformed in fundamental ways. According to the estimate of McKinsey Global Institute, a yearly contribution of AI to global produced value could be as high as 7 % of the world’s GDP, unfolding gradually in the coming years. This is an enormous boost to the world economic product and if harnessed properly can enhance prosperity in many places, including in CEE.

However, the application of AI to many sectors will bring also many challenges and risk of disruption to which national economies and their leaders will have to react. Transformation of the nature of work in many sectors and robotization will mean that many workers will be displaced from their current jobs. While predictions vary as to how precisely the AI will transform the economies and to what extent the labor market will be affected, it is presumed that the impact will be nothing short of fundamental. It might be worth pondering the potential adverse effects of the AI to the labor market now since the unfolding of AI revolution with both enormously positive gains but also concomitant negative economic side effects can come relatively quickly.

There are at least three areas where one could think a progress made would help prepare for the coming challenges :

First, it is clear that supporting the sector of lifelong learning should bring dividends on many fronts. Many displaced workers will likely not be able to find a new job in the same sector where they worked previously. Here the retraining – possibly subsidized one way or another by the governments – could help. Furthermore, a more complex response to boosting the whole sector of lifelong learning – such as through various tax-related schemes that would encourage private sector provision of retraining and encourage the flow of resources to the sector – could also help.

Second, large infrastructure projects which are still needed in many CEE countries would help absorb released workers – however, financing of such projects will be circumscribed by the usual fiscal constraint. Hence even more cautious than usual fiscal policy stance in the coming years would help prepare the fiscal position of individual countries for extraordinary expenditures should AI-related labor displacements prove significant and a launch of infrastructure projects be chosen as one of the solutions.

Third, but perhaps most importantly, promoting entrepreneurship and supporting various schemes to help start-ups would go a long way towards creating ground from which many new enterprises can spring ready to absorb displaced workers. Since the industry is particularly vulnerable to labor displacements due to likely future robotization and while start-ups in that sector are particularly demanding undertaking, innovative ways to help such start-ups would be called for. An increased flow of resources to the R&D sector could help CEE countries further reduce the gap from the technological frontier; the effective collaboration between business and universities would mean that advances in research would translate into commercialized products. Additionally, small business and self-employed workers should be particularly encouraged through various schemes. Also, more philosophically, support of Small business could be an effective recipe for many ills which the current integrated economic system brings, along with prosperity.

AI-related revolution is right at the corner. In order to fully realize its potential, which is enormous both for economic prosperity as well as quality of life, it is time to ponder the best medium-term solutions to some of the downsides that it is likely to bring along with the great benefits.

Vladimir Zlacky

LookingEast.eu

26.october 2019

by Vladimir Zlacky | Jun 18, 2019 | Bratislava | News

Artificial intelligence (AI) fueling 4.0 Industrial Revolution has put on center stage several questions in the context of a converging economy, such as the one of Slovakia. Will the introduction of AI help the main pillars of the Slovak economy such as FDI-owned manufacturing industries? Which policy challenges and risks will it bring to the fore?

In a nutshell, for Slovakia AI introduction will likely be good and bad news at the same time. Coming introduction of AI technologies will drive down labor to output ratios on a company level and will thus mean that the labor cost will become much less important for investment decisions. On one hand, it will be good news because AI introduction will lead to a reduction of the importance of labor costs in certain sectors as the competitive factor and will blunt incentives for the existing manufacturing plants to leave Slovakia and move eastward driven by convergence– as it might be happening otherwise.

However, it also means that for a country such as Slovakia it will likely be much harder to acquire future FDI since the advantage of low labor cost as a competitive factor will be significantly reduced in AI intensive sectors. Things like quality of the business environment, tax regime or reduction of country risk through a better institutional environment will matter relatively more. More generally, it means we might thus move into the world where soft factors such as business/institutional environment matter more for investment decisions than the labor cost.

Sector-level wise, at the national policy level in Slovakia, one should focus efforts to attract FDI in areas where AI will not make much difference and a ratio of wage bill to output remains significant (such as tourism, hospitality, some other services). This is because attempts to lure FDI – bar strong improvements in the institutional arena – where wages do not constitute a high share of output anymore would likely prove futile.

AI likely to suppress incentives for FDI

More generally, the application of AI to manufacturing will likely lead to a reduction of downhill FDIs globally in the future. A little speculatively, pending AI machines installation projects may even already explain some of the recent fall in cross-border FDI in 2018. The world with much less FDI puts a premium on domestic economic policies to nurture home companies and fuel domestic economic growth.

The quality of human capital will continue to matter and its relatively low cost may be a driver for certain inward investments (such as shared services) in sectors where there is still a high share of labor compensation on output. Investment in the country’s human capital should thus remain important – after-all, AI machines dominated factories will require the presence of super-sophisticated managers/engineers. Tax incentives, among other reform measures, for support of the sector of lifelong learning, would go a long way towards further beefing up the domestic educational sector which should educate such experts.

Given that future incoming FDI will likely slow down – at least in those sectors where robots can replace humans – much higher effort should be focused on building a domestic enterprise sector via start-ups support and different schemes of nurturing domestic entrepreneurship.

Less developed world: Convergence endangered?

If the simplified discourse above is correct, implications of it do not seem necessarily only positive for less developed countries and challenges they are facing. Given that their business and institutional environments are relatively weak and the labor cost is a primary competitive advantage factor, FDI in sectors where robots can replace humans will likely be not lured to such areas to the same extent as before. Some FDI factories might even migrate uphill to areas with better business, tax and institutional environment since the importance of labor cost will be so drastically reduced. Bottlenecks on markets with super-sophisticated managers/engineers to run such AI-intensive factories may contribute to that as well. It could also lead to the race to the bottom regarding environmental standards as less developed countries try to compete on non-labor cost factors. Whether AI heavily applied to the manufacturing sector also means a higher probability of middle-income trap incidence for countries such as Slovakia is worth pondering too. Focusing on substantially upgrading the business and institutional environment and supporting domestic start-up scene in middle-income countries like Slovakia could certainly help avert such scenarios.

Vladimir Zlacky, LookingEast.eu

Bratislava, 26 JUne 2019

by Vladimir Zlacky | May 4, 2019 | Bratislava | News

It is brands, Economist !

Typically, many economists have not always fully appreciated business disciplines of softer nature – marketing as a field quickly comes to one’s mind. Yet, it is enormous how significant is the value astute marketing people can create for the national economy. They not only help salespeople of companies penetrate markets home and far abroad but through strategic brand-building enormously enhance the economic value of production.

It is not rare that a branded product – a product which carries a recognized and reputed brand – can sell for a multiple of price of a generic product. This is typically a result of concerted brand-building efforts by and within a given organization. Consistent and attractive visuals and designs of products, thought-out media advertising, marketing events of many kinds, aligned organizational behavior – these all can come under a rubric of brand-building. Yes, brand-building also entails a cost but typically astute marketing people can create the brand where a brand price premium can exceed the incurred cost substantially.

When the national economy has many high-quality brands this might also have macroeconomic implications. It can mean that countries with the most astute marketing people can see their GDP enhanced by these strategic marketing efforts more than others. This is something not completely obvious when one thinks about the role and the effect of marketing in the economy (one would think perhaps, in a first cut, of mostly zero-sum game when analyzing marketing effects within a sector). Furthermore, branded products command a much higher degree of customer loyalty – this has implications for competitiveness of the national economies. Just think what a 20% appreciation of domestic currency does with the competitiveness/profit margins of commodities exporting countries vs. highly branded products exporting countries. The latter economy is clearly much more robust to currency value shocks.

When looking at this issue via the glasses of somebody born and living in a Central-Eastern European (CEE) country one has to appreciate the road traveled since the inception of transformation of these economies to a market model also in case of local marketing activities. The marketing area was extremely neglected during the socialism regime as very little advertising and brand-building took place. During the last 30 years enormous progress was achieved as demonstrated by springing up of many attractive brands in these economies, although most of them are only of local significance. Obviously, not all progress was domestically driven but rather the effect of inflow of FDI, which brought some marketing practices, and of other foreign influences cannot be underestimated.

Yet, while the marketing expertise in the CEE economies has advanced, further improvement could be achieved by bringing business education closer to business people in these countries. Offshoots of Western business schools could perhaps find this high growth terrain of converging economies of CEE a very lucrative base for spreading their influence. If establishing their branches in CEE, they could further nurture Western management practices and culture in these countries. Besides so important marketing field as noted above, other creative areas such as general/strategic management, leadership and people management or entrepreneurship could thus be supported in CEE too. By means of not only degree programs but of various executive and evening/weekend programs such schools could help local business people grow in expertise. Spearheading entrepreneurial and start-ups culture in countries where FDIs have been a typical engine of development to date should also be commended if such school(s) appeared in the region.

Given that human capital – also that entailing best business practices – seems one of the bottlenecks of further economic development in CEE, the government could also contribute by introducing tax incentives for the whole sector of lifelong learning, including business school education.

Vladimir Zlacky

LookingEast.eu

May 4, 2019

by Vladimir Zlacky | Jan 9, 2019 | New York City | News

Nearly three decades ago, at the onset of transition, ex-socialist countries’ enterprise sector was lagging severely behind that in the developed West – machines, and technology more broadly, were largely obsolete, labor productivity low and managerial techniques inadequate for a modern economy. Restructuring of enterprises i.e. installation of new technologies, improvement in quality of products, introduction of new processes, upgrade of the labor and management and exploration of new markets was crucial for the success of transition.

While early macroeconomic policies were designed to address macroeconomic disequilibria, they in combination with policies for micro-level adjustments were to conduce to enterprise restructuring. In many transition countries, foreign direct investment (FDI) was the key solution towards the task of enterprise restructuring. This was because – at the inception of transition and ensuing first years of reforms – there was a severe lack of capital, inadequate domestic technology and underdeveloped managerial talent.

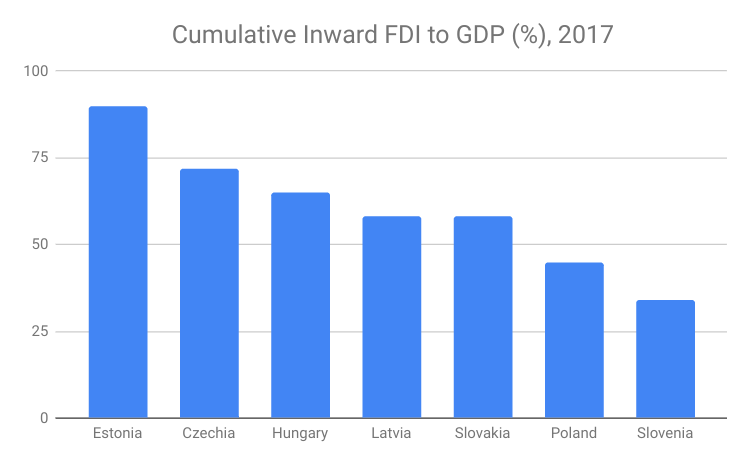

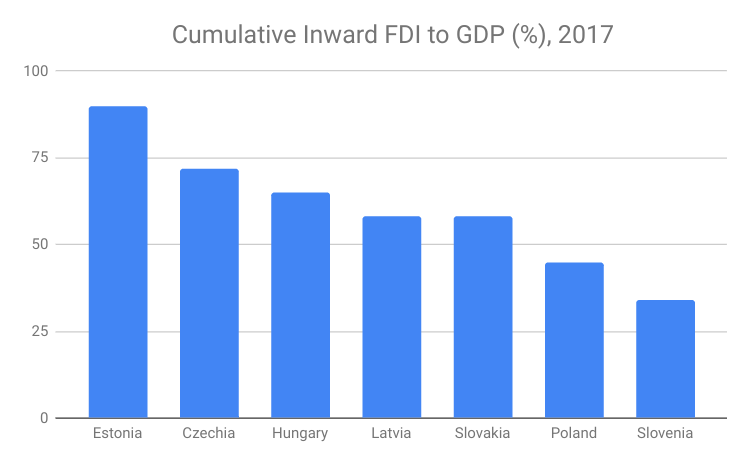

This demand for FDI capital led to a huge inflow of foreign direct investment to the transition countries when literally hundreds of billions euro worth capital led to acquisition of a substantial share of domestic productive capacity in these countries. Relatedly, some numbers will demonstrate that – in a small economy of Estonia by 2017 cumulative inward FDI reached nearly 90% of its GDP (net position being 61% of GDP). Other countries became significant hosts of FDI as well – inward investment in Czechia were 72% of GDP while that in Hungary was 65% of GDP by 2017.

Source: OECD

It seems fair to say that up to now the FDI has been the main driver of growth in most post-socialist countries. However, these countries have matured by now – a pool of managerial talent has grown both by quantity and quality, countries have been integrated into international sales chains, capital for sound projects is available from private equity groups or banking sectors. Domestic R&D and science have moved closer to the world’s frontier in some countries and the quality of managers and other experts is such that the technological know how can be imported easily. In other words, investment landscape in at least most advanced countries of the region has changed and is conducive to formation and growth of world competitive but domestically owned companies.

Hence, it seems that at the end of 2010’s the big “growth” question is which model of growth to promote ? To further a model based on FDI or attempt to nurture domestic enterprises ? As often-times is the case, the middle road will likely deliver the best results. FDI still brings most modern managerial know-how and corporate culture, tested processes, high quality products and connection to existing markets – all valuable attributes of a modern enterprise. It would be a mistake to discourage their inflow.

However, should generous FDI incentives be kept in many countries or these resources be rather targeted to creation of domestic startups and existing companies ? To be sure, domestic companies have certain advantages too. First, large domestic investment groups/enterprises are probably more keen to invest in public goods than foreign-owned enterprises. Things like very local infrastructure, education, culture or sports – investments that have spillovers – are much more likely to be supported by local big entrepreneurs than by branches of large multinational companies. Second, at times, domestic policymakers may want – through a moral suasion or otherwise – coordinate with a private sector and in such cases domestic entrepreneurs will more likely be brought on board to cooperate.

Last but not least, as Prof. Dani Rodrik1 tells us, FDI ownership shifts the bargaining power from labor to capital leading to lower wages on a company level (and may lead to lower labor/output ratios in the whole economy). In extreme case, detachment of labor from the companies in combination with perceived unfair wage treatment may lead to backlash against foreign ownership as such. A legitimacy of the current highly integrated economic system might be called into question as well. From this point of view, a more balanced economic structure – one in which both foreign and domestic enterprises co-thrive – seems to lead to more sustainable economic model.

Hence, given limited resources available, it might make sense to earmark some share of resources yet devoted for FDI incentives for the support domestic start-ups instead. Given that typical start-ups do not require much funding, a relatively large number of small starting entrepreneurs could be thus supported. One way to accomplish this is through a independently run fund with multi-source funding – perhaps partly private charity sponsored – from which the entrepreneurs could petition a support or via which various other schemes of support could be administered. Only a small share of funds hitherto available to huge FDI projects and redirected to small business could make a big difference to many individuals. The support of start-ups or small entrepreneurship would have an added advantage of pulling employees into entrepreneurship thus converting them into “capital-owners” with positive implications for social mobility, distribution of income and nurturing of entrepreneurial culture in these countries. Furthermore, this all could work as a potential recipe against the backlash against the current economic system which in its nascent form seems ubiquitous at many corners of the world.

Vladimir Zlacky

LookingEast.eu

1. Dani Rodrik, “Populism and the economics of Globalization”, Journal of International Business Policy, 2018