It is nearly three decades since the fall of the Berlin Wall which led to an upheaval in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) unleashing fundamental changes in the formerly socialist countries of the region. The task of revamping the socio-economic systems of these countries was daunting and multifaceted – the economic, as well as political systems of the Eastern bloc countries, had to be utterly transformed. The road to the envisaged market-based economic model supported by democratic politics was bumpy and far from costless. The CEE countries of the region not only had to “traverse the valley of tears”, borrowing here from Prof. Przeworski 1, when initial reforms meant to address the issues of macroeconomic disequilibria, relative price adjustments, and fundamental ownership changes led to heavy economic losses but also to undertake protracted and demanding institution-building thereafter. At least for the advanced countries of Central Europe, the transition road is basically over since – according to the economic criteria – they exhibit all features of normal mid-income market-based economies, as highlighted in the research of Profs. Shleifer and Treisman .2

The convergence of the formerly socialist countries in terms of economic output to the level of developed West proceeded at an uneven pace as the countries’ initial conditions and transformation strategies adopted by policymakers differed. This resulted in often vastly differing output and other economic outcomes’ trajectories. The Eurostat data show that the most advanced countries of Central Europe such as Czechia, which reached the level of 89% of GDP per capita in normalized prices (PPS) of EU(28) in 2017 or Slovenia (85%) are nearly closing the gap with economically advanced nations of Europe, at least in terms of the real economic output. A study by UniCredit Slovakia economists 3shows that sector-level adjustment was also rapid in the advanced countries of Central Europe and convergence nearly completed in the sector level structure. When comparison is made within sectors, however, more needs to be done so that these countries come yet closer in production to the productivity frontier of the advanced West. Other countries, such as Estonia (79%), Lithuania (78%) Slovakia (76%) and Poland (70%) are also making rapid progress in convergence.

Interestingly, the most advanced CEE countries are already reaching levels near – Italy (96%) and Spain (92%) – and are above southern European old members of the EU such as Portugal (77%) and Greece (67%). The further rapid convergence is predicated on the ability of the CEE countries to generate investment, be that of domestic source or FDI, further enhance the quality of their workforce and to reduce a technological gap with the advanced economic nations.

Although at a slower pace than during the decade in the run-up to the financial crisis in 2008-9, the CEE countries have been growing briskly this decade. According to Focus Economics, the growth in the EU(11) countries – eleven post-socialist countries of the EU – should be 4.1% this year. However, the cyclical upturn is reverting to a close in the CEE region as the expected Eurozone slow-down, labor bottlenecks in some countries, the potential fallout from Brexit as well as monetary tightening will bring an easing of the economic growth in 2019. The overall economic growth of the EU(11) region, according to the forecast of Focus Economics, will be 3.4% with Slovakia claiming the leading position with expected 3.7% annual growth ahead of Poland with 3.6% growth. With the growth in the region on the taper trajectory, further need for adopted pro-growth agendas seems imminent. According to the study by McKinsey Global Institute4 an explicit pro-growth agenda adopted by governments seems to be one of the crucial supporting factors of long-term economic success, at least when one retrospects the growth record of countries over the last fifty years globally.

Which areas of policy reforms or adjustments would most conduce to a strong growth in the medium to long term in the CEE region? Three thematic areas – business environment, institutional framework, and human capital – seem particularly worth addressing:

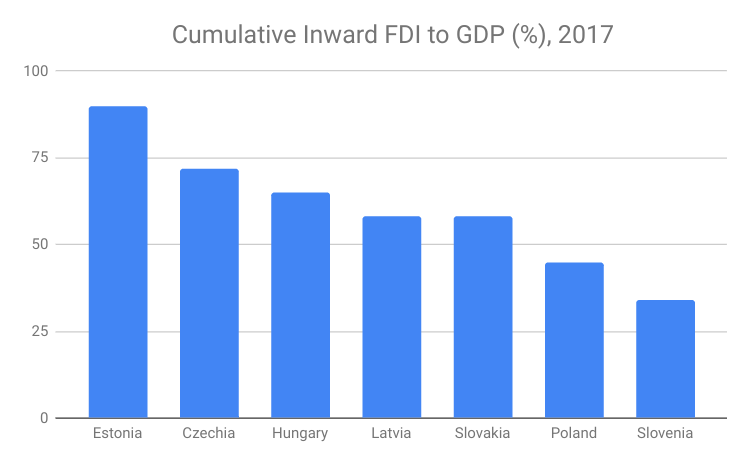

1.) Business Environment. Perhaps because of a lack of domestic capital, technological know-how and developed managerial talent, the economic growth of most countries of CEE was largely driven by foreign direct investment (FDI) to date. While very supportive of economic growth, in the longer term, an FDI-based growth model alone does not seem to be an optimal one. More balanced economic structure is needed should the countries rapidly climb the value ladder in the longer term; company headquarters rarely relegate the highest value-adding economic activities to recipient countries. The notion that there is a need for a balanced economic structure beyond the “FDI model” is further implied by the study of McKinsey Global Institute which highlights the importance of domestic corporate champions for sustained rapid economic development.

Measures such as reducing administrative burden for entrepreneurs, eradicating obstructive regulations, minimizing red tape/ corruption and putting certain public services for entrepreneurs online would go a long way towards supporting the growth of small businesses. Public-private partnerships in the area of start-ups and R&D could further lead to nurturing small business/SMEs and be a push for the development of technologically advanced firms. This would all conduce to a higher likelihood of bringing to life national corporate champions that could spearhead regional or country-wide development one day.

2.) Institutional Framework. The importance of institutions for the economic prosperity of countries is well established in economic literature, most owing to Prof. Douglas North. Property rights and contracts need to be well defined, fairly and predictably enforced for production and commerce to flourish. This area gains further saliency in the countries of the former socialist block as the institutional frameworks underpinning their socio-economic systems needed to be fundamentally revamped.

Their constitutions had to be re-written, commercial codes re-introduced/redesigned and other important laws adopted or changed. Judiciaries, public administration, and other executive bodies were in need of a reform. No doubt, the fast-evolving global economy, and its trends mean that laws in the CEE countries need to be constantly adjusted or newly written too. However, going forward, it is mostly the reforms of the public sector organizations that pose policy challenges as they will require concerted and detailed effort, oftentimes bear political costs and do not present policymaker with much low-hanging fruit. Nevertheless, in terms of public welfare enhancement – since these reforms would conduce to both efficiency and economic growth – the area of reforming institutions, bodies enforcing them and other public sector organizations is of enormous significance.

3.) Human Capital. A continued upgrade of the human capital of the CEE countries would likely significantly contribute to speeding up convergence and reaching a higher level of prosperity. While benefiting from the legacy of relatively good schooling under socialist regimes, the current educational systems of the CEE countries are oftentimes no longer keeping abreast with the modern standards and mostly lagging behind those in the developed West. For the countries to speed up convergence, they will likely find in their benefit to improve the formal educational sector and incentivize the development of the sector of lifelong learning.

Particularly, university and other higher education sectors merit further attention – currently, it seems that the foreign-owned corporate sector is substituting for local universities and higher learning in shaping the relevant skills of employees in many CEE countries. Should countries have aspirations to further climb the value ladder in production, improvements of the R&D and higher learning sectors seem vital. Particular countries’ strengths, available resources and traditions should decide whether to focus only on applied research or to attempt for breakthroughs in advanced basic research; that overly generous flow of resources to the latter could bring inefficiencies cannot be over-emphasized here.

Given the fast technological progress and an ensuing changing demand for extra skills, lifelong learning is becoming quintessential for continuous upgrade of the labor force, more reasonable income distribution and future productivity gains. Access to quality business education not only via full-time degree programs but also, or especially, through executive and evening/weekend business programs would lead to nurturing of specialized expertise / managerial talent so needed to enhance the economic value of the output and to support local entrepreneurship in the CEE countries. Targeted tax incentives could help increase resource flow to the whole sector of lifelong learning in the CEE countries.

The year 2019 will likely see an economic growth slowdown in the region of Central and Eastern Europe (3.4%). Further forecast easing of the growth in CEE is on the horizon in 2020 (2.9%). Recent policy research results, which point at the importance of explicit growth agenda adopted by governments for a development success juxtaposed on the expected slowdown of economic growth across the globe will likely bring a theme of pro-growth agendas to the fore everywhere, including CEE.

Assuming clairvoyance on the part of policymakers in CEE, should these countries aspire to keep their convergence tempo from the past, explicit pro-growth agendas – addressing the key themes of the business environment, institutional framework and human capital – might gain traction in the near future.

Vladimir Zlacky

LookingEast.eu

1.) Adam Przeworski. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1991

2.) Shleifer, Andrei, and Daniel Treisman. 2014. “Normal Countries: The East 25 Years After Communism.” Foreign Affairs.

3.) Zlacky, Vladimir, and Lubos Korsnak, 2011. “ A brief note on sector productivity in CEE: 1995-2009”, unpublished working paper, UniCredit Bratislava, 2011, available on www.lookingeast.eu

4.) McKinsey Global Institute :Outperformers: High-growth emerging economies and the companies that propel them “ September 2018 ; “ In pursuit of Prosperity”, November 2018